We Saved a Life Today. And Nobody Noticed.

[cs_content][cs_section bg_color=”hsl(0, 0%, 100%)” parallax=”false” separator_top_type=”none” separator_top_height=”50px” separator_top_angle_point=”50″ separator_bottom_type=”none” separator_bottom_height=”50px” separator_bottom_angle_point=”50″ style=”margin: 0px;padding: 45px 0px;”][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 0px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”2/3″ style=”padding: 0px;”][x_custom_headline level=”h1″ looks_like=”h1″ accent=”false”]We Saved a Life Today. And Nobody Noticed.[/x_custom_headline][x_image type=”none” src=”https://doctorlarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/We-Saved-a-Life-Today-1.png” alt=”” link=”false” href=”#” title=”” target=”” info=”none” info_place=”top” info_trigger=”hover” info_content=””][cs_text]Written by Dr. Larry

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]omething happened the other day in the ER, something that happens often probably. But this time, for some reason, I got to thinking about it.

We saved a life.

You might think that that — saving lives — is what we do in medicine, as if it belongs on a t-shirt or a bumper sticker. A t-shirt none of us who really save lives would wear, because we know intimately how limited we are, and we have memories, even nightmares, about the ones we’ve lost. But back to my story, the thing that struck me most about this life that we saved the other day:

Nobody noticed.

I know I didn’t. I had a full 20+ bed ER with more patients in the waiting room. Life-saving decision made and executed in minutes, and then I rushed off to the next patient, without giving it even a moment — much less allowing any satisfaction at the work we do.

I know I didn’t. I had a full 20+ bed ER with more patients in the waiting room. Life-saving decision made and executed in minutes, and then I rushed off to the next patient, without giving it even a moment — much less allowing any satisfaction at the work we do.

That’s fucked up. Let me tell you the story that got me to thinking.

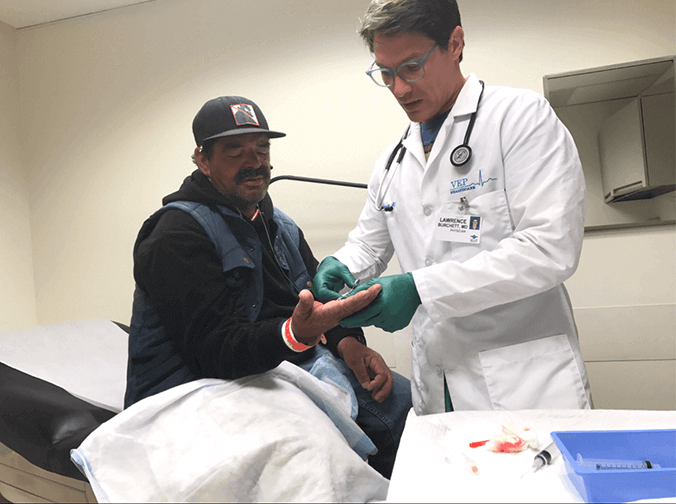

A middle-aged man with a terminal disease came in with breathing problems. When I first spoke with him in the trauma bay, he could talk to me. But a mere two minutes later, his oxygen saturation has dropped to 29 percent (normal is 100 percent), his heart rate was slowing and he had passed out. We all (the ER nurses and myself, the ER MD) immediately knew where he was going — toward the light to meet Jesus. We had to act quickly if he had any chance of coming back to us.

After clarifying his wishes with his wife (“no heroics”), we put him on a temporary breathing machine called Bipap, which pushed oxygenated air into his lungs for him through a mask, as opposed to a full ventilator, which includes a tube down your throat (although his condition was reversible, most people don’t want to be hooked up to this machine indefinitely). Within minutes, his heart rate and color improved, and he was satting 100% on this machine. And he was alive, the light at the end of the tunnel getting further away.

We saved his life. And nobody noticed.

At least, that’s what it seemed like to me. After asking the respiratory therapist to place him on Bipap, I waited a mere second to see if it worked. With the first small signs of improvement (his heart rate going up, his pale blue color getting more pink), I knew his oxygen levels were increasing and he was stabilizing. Bam, on to the next sick patient in the busy ER to make sure nobody else was dying or getting closer to the light. It didn’t register with me until later during the day that we had, in fact, saved his life.

And you know what? I felt good about it. For once, I actually allowed myself some satisfaction at the work we do. Summer 2016 will be 10 years since I graduated medical school, with countless instances of helping people, even saving lives. And it deeply saddens and disturbs me that I have not enjoyed or allowed myself to be satisfied at many of them at all. “What is this about?” I wondered.

And you know what? I felt good about it. For once, I actually allowed myself some satisfaction at the work we do. Summer 2016 will be 10 years since I graduated medical school, with countless instances of helping people, even saving lives. And it deeply saddens and disturbs me that I have not enjoyed or allowed myself to be satisfied at many of them at all. “What is this about?” I wondered.

“You didn’t do anything special.” This is my mind’s first reaction to me feeling satisfaction. Anyone could have done it. This is true. Placing him on Bipap was neither genius nor particularly skilled. It was a good call, and the right call. But most, if not all, ER docs could do it — no big deal. There is a belief, I realized, that only when you do something truly extraordinary — diagnose the unthinkable rare disease or perform the impossibly difficult surgery — then, and only then, do you deserve some praise or satisfaction.

I can feel this belief within me. I have assimilated to it during my medical upbringing. And now that I reflect on it — I find it’s a big bunch of medical cultural bullshit. We can feel, and should feel satisfied, whenever we help. Whenever we do a good job. Whenever our patients are happy with our care. Not just when we nail the big-time case. Why? Because those rare, exceptional diagnoses are few and far between. And I, for one, want to feel that feeling of satisfaction in what I do. Not the pimping of academic bookworms. The truth is, there is so much to be satisfied in with medicine.

Reassuring the young mother that the most important thing in her world — her little boy — is fine and will sleep safely through the night. Or carefully stitching the facial laceration of the teenage cheerleader, so as to minimize scarring because it matters, to her. Or sitting with the wife of a suicidal methamphetamine addict, trying to figure out some way to make things better. Although perhaps not award-winning, all of this can be very satisfying — if we let it.

We saved a life.

“But he is going to die soon anyway.” This is the second objection from the voice in my head that I am now recognizing is another form of the medical establishment. True. He has a terminal disease, one that I cannot cure. We may have delayed his death or prolonged his life, more than actually saving it. He may have had months to live; if he lived years, it would surprise me. Saving the life of a 6-month-old with meningitis, who goes on to live well into her 90s — now that’s saving a life. We may have just given this guy a few more weeks or months, if that. Not really a big deal, right?

The belief here that I am decoding seems to be that saving a life is valuable if it gives much more time, or if it cures an underlying disease. Again, I can think of many examples to the contrary. Sure, hitting the home runs of curing cancer and serious pediatric illness are particularly satisfying when you are in the business of helping people. Duh. But isn’t it also sometimes meaningful to give people more time? Maybe this man still had things left to do. Or people to say goodbye to. Or just wanted more time with those he loved, like his devoted wife at the bedside. Is there no value to him in having more precious time? I imagine in that circumstance, time matters most.

There is a temptation to see in terminal disease our shortcomings. Expected to cure it all, we doctors simply feel inadequate when we are confronted with a problem we cannot fix. A cancer that kills, for example. Some wars we cannot win, so why face a battle that threatens our own ego as a healer?

You know the answer. Because it matters, to providers and to patients. Because it’s the right thing to do. Because that’s what we do. We take care of human beings, even when we cannot cure the disease.

Which brings me to my final observation, which came to me as I gave Tom, my nurse tonight, a fist bump as we tag-teamed a facial laceration together — one person holding the skin together, the other applying the Dermabond glue. It came together quite nicely, if I do say so myself. I felt good about it, and so should Tom. And that deserves a moment of acknowledgement, and dare I say — celebration.

It feels just wrong to say we should celebrate victories in the ER. You didn’t see high-fives or a chest bump between me and the respiratory therapist when our patient came back to life on Bipap. We don’t go out to the bars after our shift to recount how we helped people (if we do go out, it’s usually a coping mechanism for processing the difficult patients and the frank trauma we witness). It’s as if the seriousness or gravity of the work makes it inappropriate to be emotive or emotional, like we are all supposed to be some disconnected, detached physician, unaffected by human feeling.

It feels just wrong to say we should celebrate victories in the ER. You didn’t see high-fives or a chest bump between me and the respiratory therapist when our patient came back to life on Bipap. We don’t go out to the bars after our shift to recount how we helped people (if we do go out, it’s usually a coping mechanism for processing the difficult patients and the frank trauma we witness). It’s as if the seriousness or gravity of the work makes it inappropriate to be emotive or emotional, like we are all supposed to be some disconnected, detached physician, unaffected by human feeling.

Yet the fact remains that we kicked some major ass today. We saved a life and stomped out disease. And it’s not wrong to pat the team on the back for a job well done — the RT for applying the life-saving breathing device. Yes, any RT could have done it, but the fact remains that ours did it, and did it correctly to get the job done. Nice work.

I could go on, but this is the big point: Medicine still has the potential, the richness, to be profoundly satisfying. But it takes allowing these moments, what healing and service mean to the patient, to affect us. It’s probably easier to detach in the ER, to never let any of our patients affect us. Then it doesn’t hurt when they die, or when they are mad at us. But then we miss out on all the good stuff, too. That look in the eye of another human being when they trust you and you can genuinely say, “You are going to be ok. I am going to take care of you.”

What a way to save lives, kick some ass and, for once, feel truly satisfied.[/cs_text][x_gap size=”50px”][/cs_column][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/3″ style=”padding: 0px;”][x_widget_area sidebar=”sidebar-main” ][x_widget_area sidebar=”ups-sidebar-adoption-services” class=”man”][/cs_column][/cs_row][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 0px 0px 30px;border-style: solid;border-width: 1px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px;”][cs_text]

Featured Content

[/cs_text][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][cs_section parallax=”false” separator_top_type=”none” separator_top_height=”50px” separator_top_angle_point=”50″ separator_bottom_type=”none” separator_bottom_height=”50px” separator_bottom_angle_point=”50″ style=”margin: 0px;padding: 20px 0px 0px;”][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 0px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px;”][ess_grid alias=”featured_content”][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][/cs_content]